A Brief Analysis of von Donnersmarck’ The Lives of Others (2006)

What makes The Lives of Others both powerful and deeply moving—above all else—is its form: a minimalist form that, within a minimalist content, conveys the terrifying brutality of totalitarianism in East Germany with exceptional subtlety. The film avoids noise, theatrical exaggeration, or chaotic dramatization, and instead impresses the viewer through the quiet horror of a “banal but infernal everydayness.” It immerses us in the ordinary-yet-hellish atmosphere of East Germany during the long era of its Communist totalitarian regime.

Following Germany’s division during the early years of the Cold War, Berlin emerged as a ghostly city split by a wall—physically located in East Germany but with half of its territory belonging to the West. The Berlin Wall became the most vivid symbol of the hellish world “beyond the wall.” Despite its contradictions and brutalities, capitalism—from then until today—has managed to preserve at least a minimal space for freedom of expression and relatively broad liberties in lifestyle and social behavior. But until its collapse, East Germany had become one of the most fearsome states of the Eastern Bloc. It was as if the spirit of Nazism, having shed its former skin, had once again spread across the country—but this time without the grandiose spectacle of fascist pageantry, fiery ceremonies, or thunderous slogans. Instead, a cold grayness covered everything, and fear governed all human relations. For years, East Germany falsely promoted itself as an economically advanced society despite its political repression. In reality, it had built an enormous surveillance apparatus—one of the most pervasive in modern history. Through the Stasi (State Security Service), a powerful web of informants was woven into everyday life, where anyone—friends, neighbors, even family members—could be spying on you. The constant fear that anyone you knew—whether close or distant—could suddenly reveal themselves as a ruthless informant, was far more terrifying than simply being arrested by the police. Espionage wasn’t just a political threat; it destroyed every form of intimacy—friendship, love, and, ultimately, any human desire to truly live.

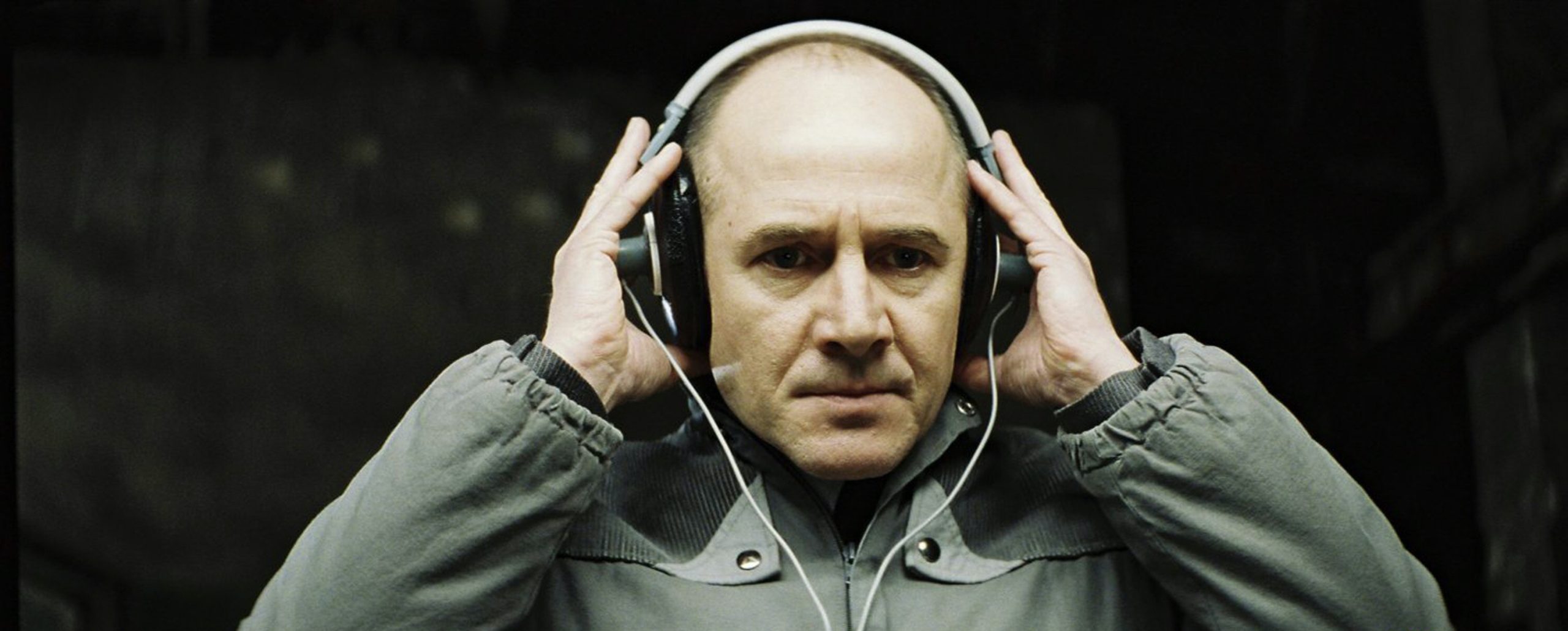

The central theme of The Lives of Others revolves around a group of writers seeking to publish an article about the alarming rise in suicide rates in East Germany—an issue that not only reflected grim reality but also signaled a deep societal despair that had permeated countless lives. Within this setting, the film focuses on a circle of artists—particularly a playwright and an actress—who are both under surveillance by state security and simultaneously being spied on from within their own intellectual circle.However, this dimension is less emphasized in the film than another: the gradual transformation of an intelligence officer assigned to eavesdrop on the intellectuals, and his eventual mental—and then practical—alignment with them, without their knowledge. This inner shift leads to his downfall within the ranks of the secret service, as he is demoted from a high-ranking officer to a lowly position inspecting letters alongside other minor employees.After the fall of the communist regime and the end of its suffocating control, this former Stasi agent takes on a menial job delivering advertising flyers to residential buildings—a symbolically degrading and physically demanding task. One day, as he passes a large bookstore still oddly bearing the name “Karl Marx,” he notices a prominent photo of the writer he once surveilled. The writer has published a book titled The Lives of Others. The officer enters the shop, sees the book, and discovers that it is dedicated to him under his surveillance codename. In a beautiful and striking moment of dialogue, when the bookseller asks him, “Is this a gift?” he quietly responds, “No… this book is for me.”

The artist, having observed the actions of the intelligence officer from afar, had discovered his codename in a special archive created after the fall of East Germany—an institution meant to inform citizens about who had spied on them. By dedicating his book to the officer, the writer was expressing gratitude toward the man who, through his quiet defiance, had prevented his arrest and indirectly enabled his eventual fame. At the heart of the story is a subtle triangular relationship between the writer, his actress wife—who is coerced into spying on him—and the officer who observes them. Through understated and unembellished interactions, the film evokes the psychological atmosphere of life under a totalitarian regime.

Despite criticisms that The Lives of Others does not fully portray the grim reality of East Germany, it arguably captures a deeper truth. Unlike many post-communist Western films that rely on sensationalism, this work focuses on the persistence of human connection—even in the heart of a brutal system—and in doing so, reveals the process through which humanity is stripped away in such regimes. Its realism—expressed not through heavy dramatization, but through restrained acting, minimalistic staging, and quiet symbolism—offers a profound, not merely literal, depiction of life under oppression.

A Brief Analysis of Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’ The Lives of Others (2006)

This is a machine-assisted English translation of a note by Nasser Fakouhi. The original text is available at the following link: