In these half-ruined mountains and plains, where here and there the oak trees still stretch their “hands in supplication” toward the sky; among a people bewildered by what is befalling them; amid the clamor of engineers, experts, and technocrats who believe their work to be an essential act of salvation for the land beneath their feet—the plains, the trees, and life itself. And yet, the living—armed with both hopes and curses—have come to greet them. Among the laborers and villagers, who in a trance-like state of wakefulness, somewhere between joy and sorrow, rebellion and helplessness, break the oak trees and turn them into charcoal.

And while we are ostensibly witnessing “progress” in the form of dam construction—embodied in the arrival of a cold, lifeless, grey monstrosity meant to serve as yet another sign of our national advancement—within all this mad, fragmented, relentless, and incomprehensible world, there seems to be only one pure and sane soul remaining: a thinker and a lover, a destitute philosopher—the last “human” in the world. A man in love who, even after decades, still sees the graceful footsteps of his lost beloved tracing the foothills and weaving through the green oak trees: the eternal Asad.

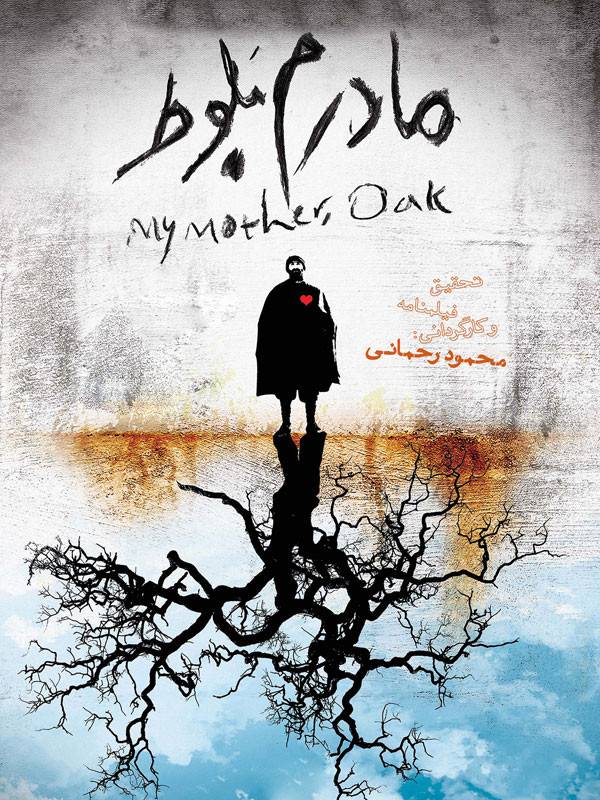

The narrator of this unbelievable yet familiar and ordinary tale is a young filmmaker who understands the people of his land: Mahmoud Rahmani, a young man whose life spans the same years as the Iranian Revolution. Like many of his generation, he waits with longing—for the land he lives on to flourish, for the thousand-year legacy passed down from ancestors to endure and reach the generations to come. Rahmani mourns for the oaks, hoping they will survive and not be sacrificed at the feet of a hard concrete beast, so that the memory of this once-lush and now-devastated plain does not vanish forever.

Who knows? Perhaps one day this plain will bloom again—once more filled with simple, joyful people who love the oak trees. People who work hard and cherish brief moments of rest under the shade of a tree, sharing bread and cheese without worrying about mortgage payments, half-built homes, bank accounts, unrealized fortunes, or the false heavens that now overwhelm and stain their lives.

Asad, however, is old now—his life spent in toil, suffering, and loss. His eyes are dim and always hold the shimmer of unshed tears. His face is weathered and deeply lined, his hands calloused and rough, his body scarred; the weight of life has crushed his bones. Asad loves the oak trees, yet like the other laborers, he dismembers his beloved, burns her, and turns her into charcoal. Asad is merciless—but it is the world that has made him so.

Still, somewhere deep within, he longs to be the same mad, wandering youth who once sat atop the hills, gazing down to watch his beloved pass below, singing to the wind from a heart full of longing. Look—there she is: the girl. Asad’s only remaining memory. The girl who, once upon a time, might have become his bride. The girl he was denied, because even then, Asad was Asad—poor, displaced, and unseen.

And today, Asad has no companion left but the oak trees—those, like him, who have raised their hands toward the sky, clinging to the hope that perhaps a miracle will arrive from the unseen and save them from being drowned in the waters the soulless grey monster seeks to submerge them in. But no miracle will come. Asad must sit and watch as his lifelong companions die—just as they, in turn, will witness his disappearance. The waters—those once life-giving waters—may now become a veil separating friends from one another.

There will be no salvation. The oaks will drown. And Asad, too, perhaps will perish in waters stirred by his own tears, in a pain that devours him from within and without. Perhaps Asad has already died; his song slowly fades beneath the clamor of engineers and laborers building the dam. Asad becomes eternal—resting beside the oaks, somewhere in the depths of those quiet but tormented waters imprisoned behind the grey, soulless beast—his weary body surrendered to the memories of his youth.

Look: the eternal Asad has finally reached his beautiful beloved.

This text is a translation assisted by artificial intelligence of a commentary by Nasser Fakouhi. The original note is available at the source below.