Liliana Cavani (b. 1933) is one of the few contemporary Italian filmmakers who, like Pier Paolo Pasolini, Marco Ferreri, and to a lesser extent Bernardo Bertolucci, pushes her cinema to the outermost limits of audience endurance in order to force them to confront “unseeable” realities. This is the same path Pasolini took with Salò (۱۹۷۵), Ferreri with La Grande Bouffe (1973), and Bertolucci at times with Last Tango in Paris (1972) and 1900 (1976). Cavani follows suit with films such as The Night Porter (1974), Beyond Good and Evil (1977), and most notably, The Skin.

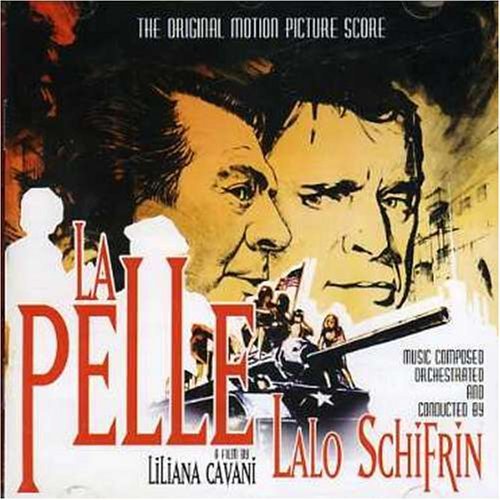

In The Skin, we encounter a genre that lays bare the “evil” and “ugliness” of war and the horrifying profiteering of human beings in their rawest form. The film is based on a novel of the same name by the renowned anti-fascist Italian writer Curzio Malaparte (1898–۱۹۵۷), published in 1949. The story is set in Naples near the end of World War II (1944). In a brief but striking scene, a father—joyful at the arrival of American forces to liberate Italy from fascism—jumps in front of a U.S. tank to greet them, only to be accidentally and indifferently crushed under its treads.

The child survives, and the American officer, visibly disturbed, expresses his regret to the Italian commander (played by Mastroianni), who responds calmly, “This too shall pass, very soon.” The camera, with a kind of unapologetic audacity and without any censorship, captures the brutally crushed body with extraordinary realism—showing only a hand still waving joyfully as the last trace of life. Throughout the film, as in her other works, Cavani recounts—one by one—those very truths that victors would prefer to remain hidden, lest they spoil the “taste of victory.”

This direct and unflinching confrontation with reality invites extensive discussion and analysis, but it undoubtedly cannot be used to deny the reality itself. The liberation of Italy from fascism by American forces must be understood alongside the fact that Italian mothers were forced to sell their children for a few packs of cigarettes, simply to avoid starving. A non-dualistic approach is essential when engaging with such complex realities. However, a critical question arises: does depicting reality in the raw and unsettling manner Cavani employs in this film—and in her other works—or as Pasolini does in Salò, inherently amount to a glorification of violence? This is a question that demands deep and nuanced debate.

This is an AI-generated translation of a note by Nasser Fakouhi. The original text is available at the following link: